- Posted on

- • Business

Thank the Gods for a falling Sterling?

- Author

-

-

- User

- aydin

- Posts by this author

- Posts by this author

-

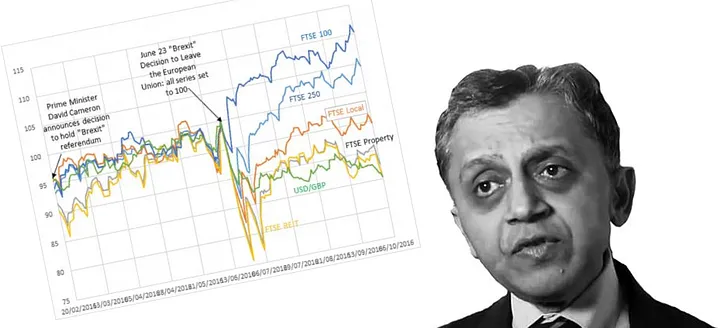

There has been much debate surrounding the rout against the British Pound since the UK’s vote to leave the EU on June 23rd. One interesting (albeit largely solitary) voice on this is that of the eminent economist Ashoka Mody who commented in the Independent that this is actually all good news for the UK.

It goes without saying that as former IMF economist and eminent visiting Princeton professor, that he is far better placed to pronounce on the matter than most of us.

However, there are a few structural corollaries worth making to his argument that this currency correction is not only overdue, but will benefit the UK in the medium to long term.

- “The UK will benefit from the loss of FinServ and overheated property asset prices.” — He is right that a more balanced economy is attractive, however this belies the pain to UK coffers, employment, and wider trickle down effect from the loss of such a significant part of the UK industry. In addition, a balanced economy requires a move to a wider breadth of high tech manufacturing, software and other professional services whilst the austerity budgets of the last 6 years have taken their toll on domestic education that this relies on. The UK has no serious policy on technology and science, and has no credible apprenticeship programmes as do competitor economies such as Germany. The Deutsches Volk are far better prepared and their nation structured in a way that could benefit from the loss of FinServ leadership, as Prof Mody rightly warns the UK appears to be heading for.

- “Britain within the European Union became a magnet for speculative international financial capital.” — Offloading the risks of such business can be dealt with by having separation of retail and investment banking — devaluation of your currency and loss of tax revenues was not a necessary component of managing this, surely?

- “British producers lost competitiveness at home and abroad.” — The argument that a weak pound makes for a stronger export is interesting if your product sells on price, rather than quality. The UK has long left the basket of countries able to compete on price (heard of China, Vietnam, India anyone?). Worse, for the high tech manufacturing that the UK needs in order to compete with peer nations such as Germany and Switzerland, source materials such as microchips and other high value components, the input costs have all just gone up almost 20%. Add to this the increased difficulty in recruiting global talent that UK employers look likely to suffer , and it is arguable that the current government’s intended immigration policy is far more likely to be a drag on competitiveness for UK business than a GBP:USD at 1.4 as it was before #Brexit.

- “As a simple matter of arithmetic, the people of Britain were not richer before Brexit. To the contrary, they were living beyond their means.” — Erm, I don’t understand. The broader consensus amongst most economists has always been that the UK was living beyond it’s means due to almost uncontrolled access to cheap credit and low productivity, not a strong Pound? Relying on a weak Pound to reverse this is surely financial engineering, and doesn’t change any of the economic and structural fundamentals of the nation.

- “After Brexit, Carney’s drumbeat about the need to protect the economy through lower interest rates and quantitative easing was evidently misguided.” — This is unfair. He had to respond urgently to market shock in the political leadership vacuum and lack of any appropriate fiscal response.

- “All these years, however, the strong pound hurt job creation and investment in productivity growth.” — I disagree. Decades of under-investment and policy vacuum in appropriate industrial and scientific skills, infrastructure and companies by a series of governments packed with History and PPE graduates leaves the UK trailing countries like Germany who are better placed to take advantage of Industry 4.0. (note, nothing wrong with History or PPE — it’s just that we need more scientists and engineers in government, frankly)

- “If the pound is about 20 per cent overvalued, then the fuss about the laughably trivial few percentage points increase in tariffs after leaving the European Union is really beside the point.” — Again, the maths are curious. If I were running Nissan (which I am not, of course), then if facing 10% tariffs on inputs and a further 10% on exports to/fro the EU, any advantages of a UK workforce (no matter how productive they are) would have to be pretty impressive to prevent moving assembly to Hungary or Czechia — no matter what the Pound is at.

Prof Mody ends his contribution with this — “if Prime Minister Theresa May’s pivot to more investment in education makes real headway, Brexit may have broken the past political lock on policymaking and redirected the economy to a more wholesome and sustainable path.” I couldn’t agree more. However, this is a BIG if, and from the rhetoric so far alongside the impact of leaving the EU on the position of UK universities in the world, most observers are not so confident.

At today’s PMQs, Teresa May referred to the “investment” of Softbank in ARM post-Brexit. It is worrying to see the UK government describe this asset acquisition on a low pound as an investment, when domestic investment in education, infrastructure and business that the UK desperately needed before Brexit, let alone now, was what Prof Mody was rightly aspiring for the country.